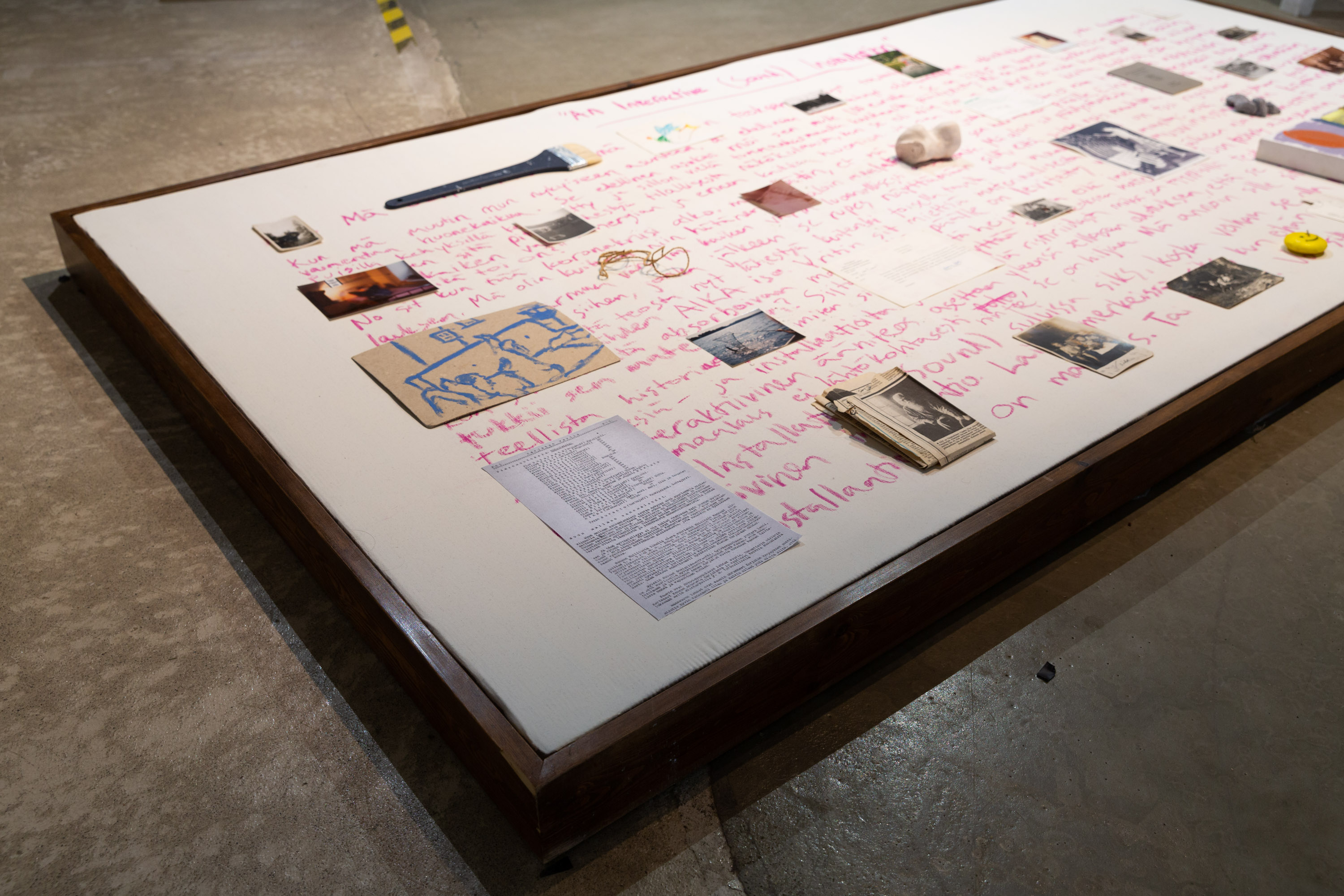

Borderlands’ counter-archive (2022)

Sound absorbing panel, artist’s frame, acrylic gesso, oil pastel, water-mixable oil paint on canvas, ceramics, drought clay, candle, cut string, brush, photographs, video, sound. Size variable.

My great-great-great-great-grand father Rimmin Ul’l’aska (1829-1918) – who was a Karelian crofter, peasant, tailor, nomadic merchant (laukkukauppias), and folk healer (tietäjä) living in a Viena Karelian village Rimpi – live modelled as Väinämöinen on Akseli Gallen-Kallela's second edition of the famous Aino-triptych (1891). In that context, Väinämöinen is the main character of the Finnish national epic Kalevala (Elias Lönnrot, 1st ed. 1835), which was constructed and edited from oral folk poetry, collected originally, and mostly from Karelian speaking Karelian people. Hence, both of the works can be understood through the interpretation matrix of cultural appropriation.

Historically, both the Aino triptych and the Kalevala have been significant building blocks of the ‘mythical history’ of the Finnish nation-state, and the Finnish ethnic and racial whiteness. The artworks are the most important events in the ideological, cultural and political discourse of Karelianism. Karelianism has justified the cultural colonization and assimilation of the Karelian people, culture and language by the Finnish elite, as well as the ‘tribal wars’ of Viena and Olonets Karelia at the turn of the 1920s, and the occupations of the East Karelia in 1941-1944. The absence of institutional language law still reproduces assimilative conditions for Karelian-speaking Karelians in the contemporary Finnish society.

In this artwork, I present photographs, objects and documents from my family's archives. The materials of the family archive mainly consist of traces of the diaspora of my Viena Karelian family, who settled in the southern Finland city, Hyvinkää, as refugees in the 1920s. As part of the archive, I combine pieces from my personal artistic history, mainly from the artworks done during my three-year bachelor's degree, in the exact-same bourgeois art institution in which Gallen-Kallela studied in the 1880s. By presenting these distantly related materials in relation to each other, and to Aino-triptych, I wish new and surprising, meaning-escaping streams to emerge from this composition.

Influenced by Gloria Anzaldúa’s thinking, I place the materials of the archive on the borderlands of the soil layers. As in the case of my relatives, information about this artwork can’t be found in the official documents of the exhibition, or in the writings of mainstream histories. This archive is evidence of the lives of the people of geographical, institutional and mental borderlands.