Ultra HD. 16:9. 12’43 minutes. Stereo. Original language Karelian and Finnish. English subtitles. Stereo sound. Color and black & white.

The starting point of the film is a historical fact: the filmmaker’s Viena Karelian ancestor Rimmin Ul´l´aška live-modeled for the second version of Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Aino Triptych (1891) in the role of Väinämöinen. Situated in three sites — Rimminkylä, the home village of Ul´l´aška; the family archive; and the Finnish National Gallery’s Ateneum Art Museum — the film is a journey through institutional and private discursive strata. Fragments of a historical exhibition, archival materials, overwritten interview and personal memories form an episodic composition that presents marginalized history rearranged.

Yritin šuaha hänet kuvah onnakko hiän kato has been screened at DocPoint – Helsinki International Documentary Film Festival‘s National Shorts Competition (2025), Oksasenkatu 11 (2025), and Kuvan Kevät 2024 (2024). The film is in the collection of Finnish National Gallery, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art.

Voices – Ul’l’aškan Vasselein Outin Annin Pentin Timo - Timo Pajunen-Noroila; Ul’l’aškan Vasselein Outin Annin Pentin Timo Mikki - Mikki Noroila

Writer, Director, Editor, Colorist, Sound Designer – Mikki Noroila

Camera – Mikki Noroila & Vieno Järventausta

Sound recording – Mikki Noroila

Additional sound recording – Olli Valkola

Sound editing and mastering – Mikki Noroila & Olli Valkola

Karelian translation – Moisejeffin Reeta

English translation – Annika Pellonpää & Miina Noroila

Producer – Mikki Noroila

Painting – Akseli Gallen: Kallela: Aino-taru (1891)

Music – Viktor Klimenko: Ajettihin Ziganaiset. Composition and lyrics: traditional. Arrangement: Viktor Klimenko. Polar Art Ky 2012.

Album: Emigrant - Riemuvuodet 1965-2012. Universal Music Oy (c) 2012 OY Emi Finland AB.

Archive materials in order of appearance –Akseli Gallen-Kallela, after coming home from Africa, in Tarvaspää garden with his dogs and the painting Cheetah. The photograph collection of Akseli Gallen-Kallela.( 1914) Possibly Mary Gallén in a lake posing for The Aino Myth. Year unknown, the photograph collection of Akseli Gallen-Kallela. President Urho Kekkonen, Prime Minister von Fieandt opposite the president, and the Board of the Bank of Finland in the dining room of the Bank of Finland. Photographed by Fred Runeberg. Helsinki City Museum. (1957) Noise excerpts from interview made by Pertti Virtaranta, and question in overwritten text. (1961) Häidenvietto Karjalan runomailla. The Kalevala Society. (1921) – Digitizing and digital post-production National Audiovisual Institute KAVI. (2021) Uljaskan pirtti – photograph exhibition of Rimpi´s histories. (2022) Family archive. (1920s - 1990s) Ateneum Art Museum – Finnish National Gallery. Collection: A Question of Time. (2024)

Thanks to, Šuuri passipo – Keijo Ahtonen, Pirjo Kyllönen, Jari Pajunen, Marianne Hotari-Pajunen, Timo Melentjeff, Moisejeffin Reeta, Art́on Kričja, Farida Albrecht, studio visit discussions w/ Salla Tykkä, Jaana Kokko, Diego Bruno, Azar Saiyar, Ewa Górzna; fellow students sharing courses and seminars in the Uniarts Helsinki's Academy of Fine Arts, Rimmin väet, ancestors, family, friends.

Extra materials

Master of Fine Arts Thesis – Yritin šuaha hänet kuvah onnakko hiän kato (in Finnish)

Examination of MFA Thesis by Minna Henriksson (in Finnish)

Examination of MFA Thesis by Katja Gauriloff (in Finnish)

Installation Documentation

Installation in Kuvan Kevät 24 at Kuva/Tila 4.5.2024 – 2.6.2024.

Photo by Petri Summanen.

Screener

Contact for full-length screener: mikki.noroila@gmail.com

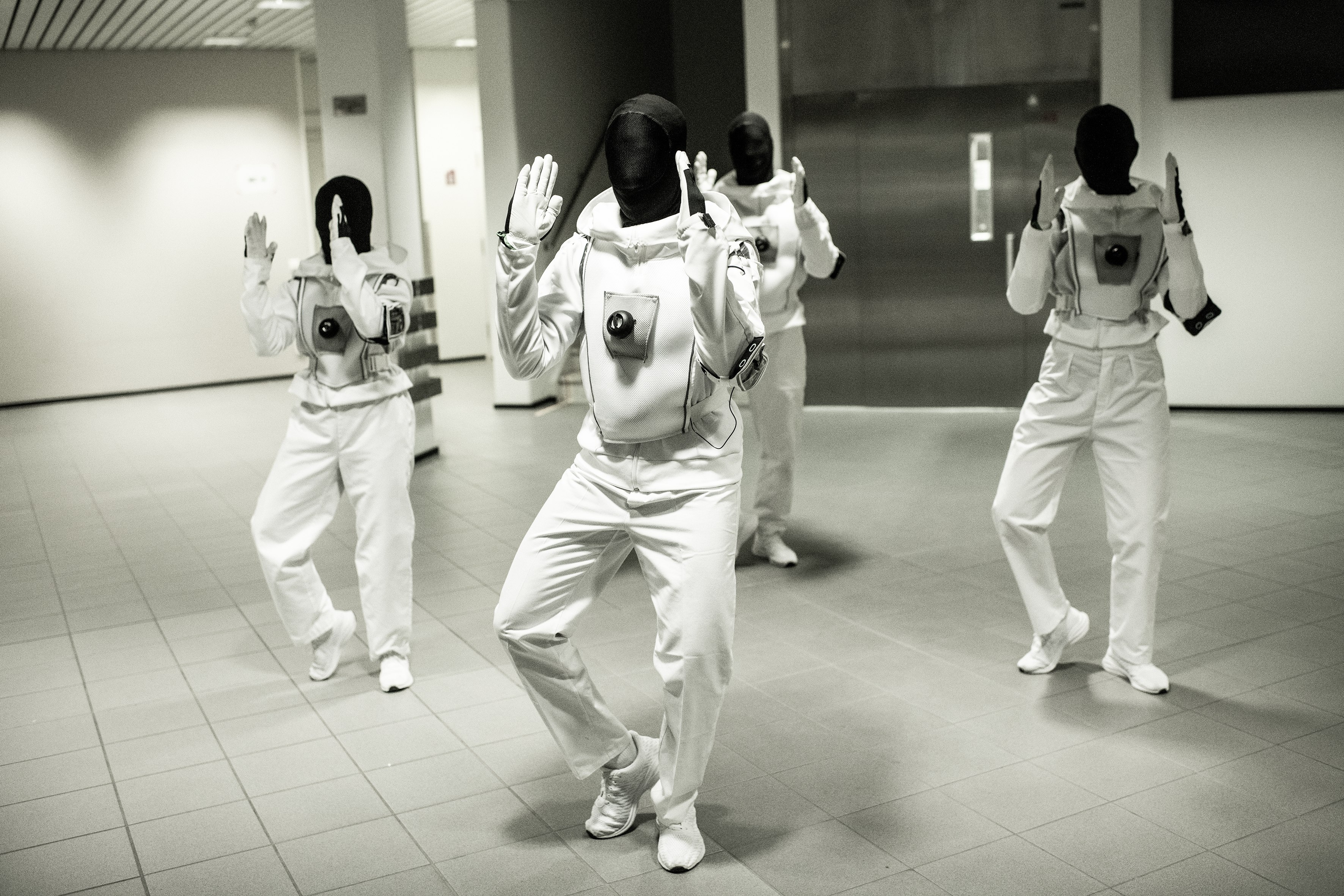

Site-specfic perfromance at Baltic Circle International Theatre Festival 2022, Helsinki

(performer & sound design)

UNDERTONE – Traces of Imminence focuses on the phenomenon of surveillance culture and totalitarianism sustained by man-made infrastructure. It reflects on how we manage our fellow species using technology. Combining experimental theatre, dance and installation, the performance takes the audience on an exploration into an imaginary reality that layers the temporalities of the past, present and future.

In the mystical reality of the performance, bodily spaces open up from personal views towards global dimensions. The performance opens up societal power structures and issues of oppression, making visible the structures that offer space and care for others, but at the same time put entire groups of people in a vulnerable position.

UNDERTONE Creative Associates

Eric Barco

Geoffrey Erista

Aju Jurvanen

Selma Kauppinen

Amita Kilumanga

Iris Laakso

Mikki Noroila

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Šulauvunnašta ta erošta (2022)

BFA degree work at the Uniarts Helsinki’s Academy of Fine Arts‘ BFA Exhibition 2022.6min, HD-video, stereo

Šulauvunnasta ta erošta is an episode from a video work-in-progress, in which I examine the historical and contemporary effect of the discourse of Karelianist-Orientalism on the Viena Karelian village of Rimpi from the perspective of the body and family histories. Rimpi is one of the three Viena Karelian villages located within the borders of the Finnish state.

The founder of the village, Rimmin Ul’l’aška, who was my great-great-great-great-great grandfather, was the live model for the role of Väinämöinen in the second version of Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Aino-triptych (1891). The painting is probably the best-known visual reference point of Karelianist art.

In the work I focus on the descendants of Ul’l’aška's Vasili's Outi's, and my grandfather’s photo archive.

The founder of the village, Rimmin Ul’l’aška, who was my great-great-great-great-great grandfather, was the live model for the role of Väinämöinen in the second version of Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Aino-triptych (1891). The painting is probably the best-known visual reference point of Karelianist art.

In the work I focus on the descendants of Ul’l’aška's Vasili's Outi's, and my grandfather’s photo archive.

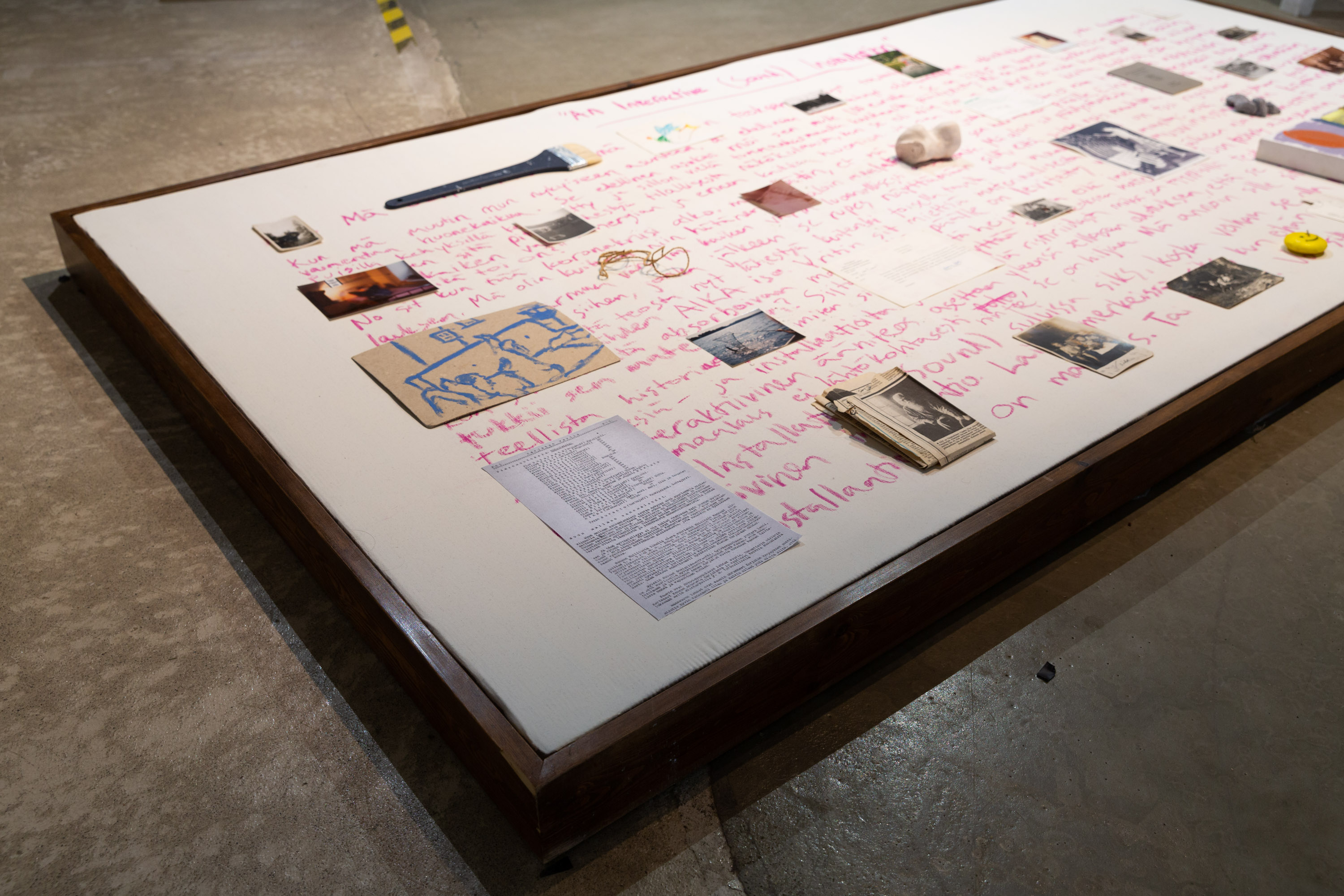

Borderlands’ counter-archive (2022)

Sound absorbing panel, artist’s frame, acrylic gesso, oil pastel, water-mixable oil paint on canvas, ceramics, drought clay, candle, cut string, brush, photographs, video, sound. Size variable.

My great-great-great-great-grand father Rimmin Ul’l’aska (1829-1918) – who was a Karelian crofter, peasant, tailor, nomadic merchant (laukkukauppias), and folk healer (tietäjä) living in a Viena Karelian village Rimpi – live modelled as Väinämöinen on Akseli Gallen-Kallela's second edition of the famous Aino-triptych (1891). In that context, Väinämöinen is the main character of the Finnish national epic Kalevala (Elias Lönnrot, 1st ed. 1835), which was constructed and edited from oral folk poetry, collected originally, and mostly from Karelian speaking Karelian people. Hence, both of the works can be understood through the interpretation matrix of cultural appropriation.

Historically, both the Aino triptych and the Kalevala have been significant building blocks of the ‘mythical history’ of the Finnish nation-state, and the Finnish ethnic and racial whiteness. The artworks are the most important events in the ideological, cultural and political discourse of Karelianism. Karelianism has justified the cultural colonization and assimilation of the Karelian people, culture and language by the Finnish elite, as well as the ‘tribal wars’ of Viena and Olonets Karelia at the turn of the 1920s, and the occupations of the East Karelia in 1941-1944. The absence of institutional language law still reproduces assimilative conditions for Karelian-speaking Karelians in the contemporary Finnish society.

In this artwork, I present photographs, objects and documents from my family's archives. The materials of the family archive mainly consist of traces of the diaspora of my Viena Karelian family, who settled in the southern Finland city, Hyvinkää, as refugees in the 1920s. As part of the archive, I combine pieces from my personal artistic history, mainly from the artworks done during my three-year bachelor's degree, in the exact-same bourgeois art institution in which Gallen-Kallela studied in the 1880s. By presenting these distantly related materials in relation to each other, and to Aino-triptych, I wish new and surprising, meaning-escaping streams to emerge from this composition.

Influenced by Gloria Anzaldúa’s thinking, I place the materials of the archive on the borderlands of the soil layers. As in the case of my relatives, information about this artwork can’t be found in the official documents of the exhibition, or in the writings of mainstream histories. This archive is evidence of the lives of the people of geographical, institutional and mental borderlands.

sound absorbing acoustic panel, wood, acrylic gesso, oil pastel, a cap.

238,5cm. x 123cm.

238,5cm. x 123cm.